Toward the Jet Age of machine learning

April 25, 2018

Machine learning today resembles the dawn of aviation. In 1903, dramatic flights by the Wright brothers ushered in the Pioneer Age of aviation, and within a decade, there was widespread belief that powered flight would revolutionize transportation and society more generally. Machine learning (ML) today is also rapidly advancing. We have recently witnessed remarkable breakthroughs on important problems including image recognition, speech translation, and natural language processing, and major technology companies are investing billions of dollars to transform themselves into ML-centric organizations. There is a growing conviction that ML holds the key to some of society’s most pressing problems.

However, this excitement should also be met with caution. For all the enthusiasm that the Wright brothers generated, nearly half a century would pass before widespread commercial aviation finally became a reality. During the Pioneer Age, aviation was largely restricted to private, sport, and military use. Getting to the Jet Age required a series of fundamental innovations in aeronautical engineering—monoplane wings, aluminum designs, turbine engines, stress testing, jumbo jets, etc.

Simply put, we needed to invent aeronautical engineering before we could transform the aviation industry. Similarly, we need to invent a new kind of engineering to build ML applications. Data-driven software development is radically different from conventional software development, as it targets complex applications domains (e.g., vision, speech, language) and focuses on learned behaviors instead of rule-based operations (e.g., training deep neural networks on massive data sets versus hand-coded if-then-else statements). Currently, very few organizations have the expertise to do this kind of engineering, and we are just scratching the surface of the potential for ML-powered technology. We describe three key challenges of this new development paradigm below.

Challenge 1: Speed and Efficiency

Modern ML applications typically involve complex models and massive data sets, requiring significant computational and storage resources. For instance, engineers at Google Brain needed more than 250,000 GPU hours to train a neural translation model for a single pair of languages (English and German), which costs about $200,000 on Google Compute Engine.[1] In response, a wide range of specialized hardware solutions are being developed (e.g., GPUs, TPUs, massively parallel CPUs, FPGAs) to improve the speed, energy efficiency, and cost of ML-powered applications.

However, effectively leveraging heterogenous hardware will require us to fundamentally redesign ML software itself. In particular, systems-aware algorithms and software are needed (i) to efficiently train models on massively parallel and heterogeneous hardware, and (ii) to satisfy service level agreements (SLAs) related to latency, power consumption, and memory footprint constraints for production deployments. Advances in hardware must be closely coupled with algorithmic and software innovation in order to develop and deploy ML-based applications in a timely and economical fashion.

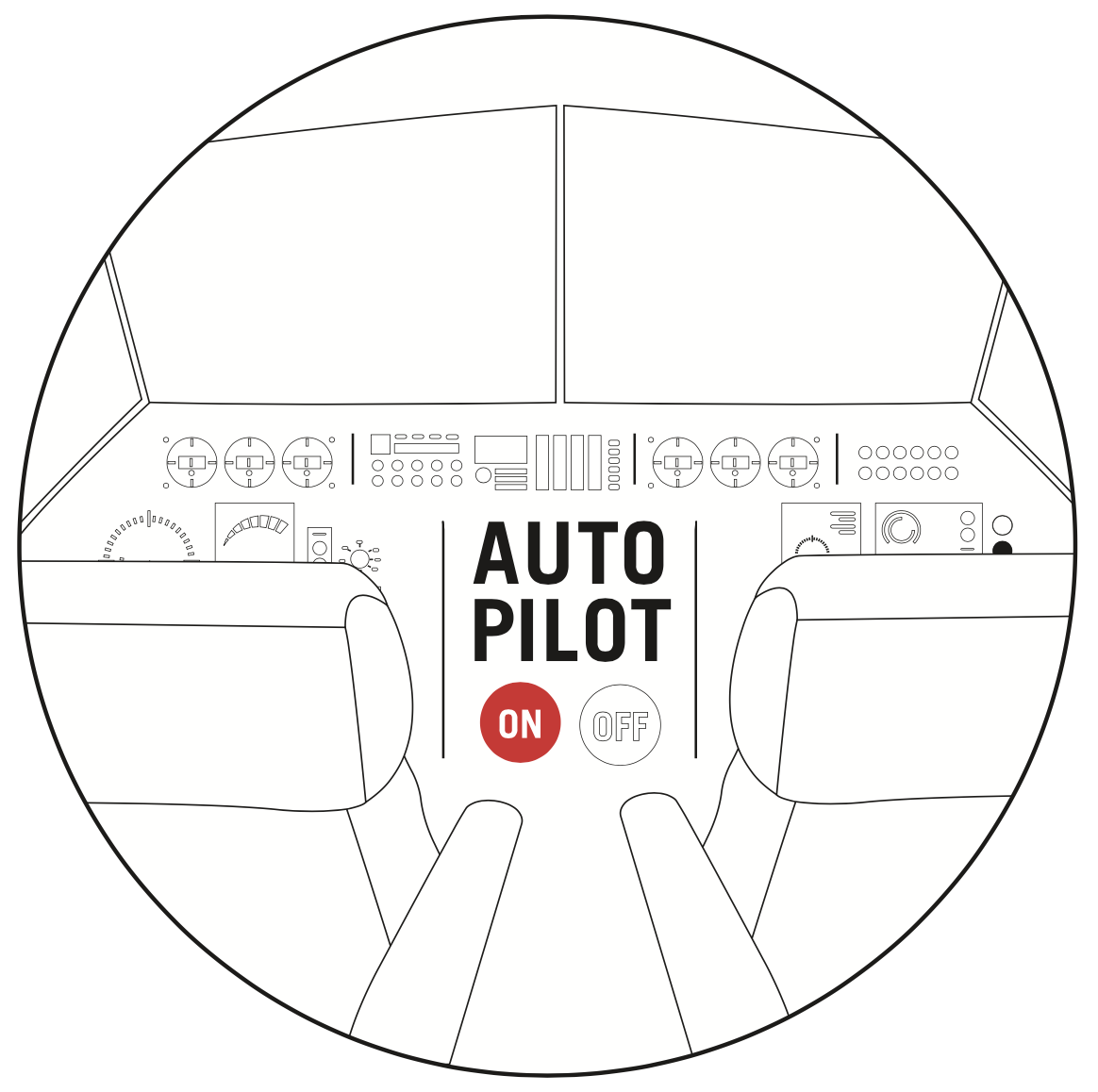

Challenge 2: Automation

In addition to being computationally intensive, ML-powered applications are incredibly labor-intensive for ML engineers to train, debug, and deploy. First, even selecting the appropriate computational platform is challenging, given the rapidly changing hardware landscape and diverse set of available cloud-based offerings. Second, the quality of an ML model is highly sensitive to hyperparameters; tuning these hyperparameters is crucial for accuracy but is often labor-intensive and expensive in computational cost. Third, utilizing parallel hardware at training time is highly non-trivial. Naively boosting computational power often does not result in meaningful speedups, and fair and effective sharing of cluster resources among users can be challenging.

To make things worse, developing ML applications is not a one-shot process: data changes over time, and therefore models and systems must adapt. Diagnosing and updating stale models is challenging, and exacerbated by the surprising difficulty (and sometimes impossibility[2]) of reproducing the behavior of ML applications. These issues are due to many factors, including (i) the statistical or “fuzzy” nature of these applications; (ii) the complexity of ML applications (e.g., pipeline jungles[3]); and (iii) ad-hoc development processes in which both code and data evolve over time with inadequate (and sometimes non-existent) controls. Given the shortage and cost of ML talent and the increased demands for ML technology, there is a pressing need to automate and simplify these development and deployment processes.

Challenge 3: Safety

As ML applications become more ubiquitous and increasingly influence societal interactions (e.g., curating news, determining credit worthiness, influencing criminal sentencing, navigating vehicles autonomously), the safety risks associated with the misuse or misunderstanding of this technology are magnified. It is, thus, critical to understand and audit the behavior of ML applications: do we understand how models are making their decisions? What is the confidence / uncertainty associated with individual decisions? Do these predictions pose immediate threats to an individual or to society? What are the broader ethical ramifications of a given ML application? What information is being used to make decisions? Is individual privacy adequately being preserved?

Unfortunately, ML applications do not provide us with straightforward answers to these questions. They are inherently data-driven and not based on simple rules, and we have a fundamental lack of understanding as to why leading ML approaches (e.g., deep learning models) even work in the first place. In addition to advancing our basic scientific understanding, it is paramount that we develop robust ML-centric engineering processes to mitigate potential safety risks. These new processes must address the complexity and uncertainty inherent to ML applications.

The interdisciplinary path forward

These challenges—efficiency, automation, and safety—won’t be solved overnight. It is clear that they touch a broad set of disciplines, and consequently devising effective solutions will require cooperation between researchers and engineers spanning both academia and industry.

From an academic perspective, we are already witnessing encouraging signs of interdisciplinary progress, as these core challenges have spurred the development of new research communities. Two notable examples are: (i) the SysML[4] research community that works at the intersection of systems and ML to design system-aware algorithms and identify best practices for learning systems; and (ii) the FatML[5] research community that brings together a diverse set of social and quantitative researchers and practitioners concerned with fairness, accountability, and transparency in ML.

However, we ultimately want to move beyond academic research, and leverage cutting-edge theoretical advances in order to design and build increasingly robust and sophisticated engineering systems. To do so will require coordination between researchers working on more abstract and theoretical problems and engineers who understand industrial processes and real-world deployment requirements. While we have a long way to go before we arrive at the Jet Age of ML, continued collaborative efforts will truly enable ML to take flight.

1 Britz et al. Massive Exploration of Neural Machine Translation Architectures, Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2017.

2 For instance, various TensorFlow operations on GPUs or multi-threaded CPUs are known to be non-deterministic; see https://github.com/tensorflow/tensorflow/issues/3103 for more details.

3 Sculley et al. Hidden Technical Debt in Machine Learning Systems, Neural Information Processing Systems, 2015.

4 http://www.sysml.cc

5 https://fatconference.org

This article first appeared on oreilly.com